Transition dipole moment

The Transition dipole moment or Transition moment, usually denoted  for a transition between an initial state,

for a transition between an initial state,  , and a final state,

, and a final state,  , is the electric dipole moment associated with the transition between the two states. In general the transition dipole moment is a complex vector quantity that includes the phase factors associated with the two states. Its direction gives the polarization of the transition, which determines how the system will interact with an electromagnetic wave of a given polarization, while the square of the magnitude gives the strength of the interaction due to the distribution of charge within the system. The SI unit of the transition dipole moment is the Coulomb meter (Cm); a more conveniently sized unit is the Debye (D).

, is the electric dipole moment associated with the transition between the two states. In general the transition dipole moment is a complex vector quantity that includes the phase factors associated with the two states. Its direction gives the polarization of the transition, which determines how the system will interact with an electromagnetic wave of a given polarization, while the square of the magnitude gives the strength of the interaction due to the distribution of charge within the system. The SI unit of the transition dipole moment is the Coulomb meter (Cm); a more conveniently sized unit is the Debye (D).

Contents |

Definition

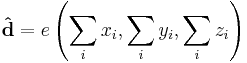

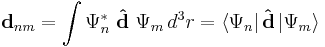

The transition dipole moment for the  transition is given by the relevant off-diagonal element of the dipole matrix, which can be calculated from an integral taken over the product of the wavefunctions of the initial and final states of the transition, and the dipole moment operator,

transition is given by the relevant off-diagonal element of the dipole matrix, which can be calculated from an integral taken over the product of the wavefunctions of the initial and final states of the transition, and the dipole moment operator,

,

,

where the summations are over the positions of the electrons in the system. Giving the transition dipole moment:

,

,

where the integral is in principle over all space, but it can be restricted to the region in which the initial and final state wavefunctions are non-negligible.

Analogy with a classical dipole

A basic, phenomenological understanding of the transition dipole moment can be obtained by analogy with a classical dipole. While the comparison can be very useful, care must be taken to ensure that one does not fall into the trap of assuming they are the same.

In the case of two classical point charges,  and

and  , with a displacement vector,

, with a displacement vector,  , pointing from the negative charge to the positive charge, the electric dipole moment is given by

, pointing from the negative charge to the positive charge, the electric dipole moment is given by

.

.

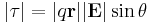

In the presence of an electric field, such as that due to an electromagnetic wave, the two charges will experience a force in opposite directions, leading to a net torque on the dipole. The magnitude of the torque is proportional to both the magnitude of the charges and the separation between them, and varies with the relative angles of the field and the dipole:

.

.

Similarly, the coupling between an electromagnetic wave and an atomic transition with transition dipole moment  , depends on the charge distribution within the atom, the strength of the electric field, and the relative polarizations of the field and the transition. In addition, the transition dipole moment depends on the geometries and relative phases of the initial and final states.

, depends on the charge distribution within the atom, the strength of the electric field, and the relative polarizations of the field and the transition. In addition, the transition dipole moment depends on the geometries and relative phases of the initial and final states.

Origin

When an atom or molecule interacts with an electromagnetic wave of frequency  , it can undergo a transition from an initial to a final state of energy difference

, it can undergo a transition from an initial to a final state of energy difference  through the coupling of the electromagnetic field to the transition dipole moment. When this transition is from a lower energy state to a higher energy state, this results in the absorption of a photon. A transition from a higher energy state to a lower energy state, results in the emission of a photon. If the charge,

through the coupling of the electromagnetic field to the transition dipole moment. When this transition is from a lower energy state to a higher energy state, this results in the absorption of a photon. A transition from a higher energy state to a lower energy state, results in the emission of a photon. If the charge,  , is omitted from the electric dipole operator during this calculation, one obtains

, is omitted from the electric dipole operator during this calculation, one obtains  as used in oscillator strength.

as used in oscillator strength.

Applications

The transition dipole moment is useful for determining if transitions are allowed under the electric dipole interaction. For example, the transition from a bonding  orbital to an antibonding

orbital to an antibonding  orbital is allowed because the integral defining the transition dipole moment is nonzero. Such a transition occurs between an even and an odd orbital; the dipole operator is an odd function of

orbital is allowed because the integral defining the transition dipole moment is nonzero. Such a transition occurs between an even and an odd orbital; the dipole operator is an odd function of  , hence the integrand is an even function. The integral of an odd function over symmetric limits returns a value of zero, while for an even function this is not necessarily the case. This result is reflected in the parity selection rule for electric dipole transitions.

, hence the integrand is an even function. The integral of an odd function over symmetric limits returns a value of zero, while for an even function this is not necessarily the case. This result is reflected in the parity selection rule for electric dipole transitions.

References

"IUPAC compendium of Chemical Terminology". IUPAC. 1997. http://www.iupac.org/goldbook/T06460.pdf. Retrieved 2007-01-15.